New Delhi, Feb. 14 -- The United States has been undermining the global trading system since 1917, when the United States entered the First World War. That year, Congress passed the Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA) to 'define, regulate, and punish trading with the enemy'. This statute conferred on the President wide-ranging powers to restrict trade between the United States and foreigners or countries considered enemies during wartime. Currently, TWEA remains the underlying legislation only for sanctions against Cuba. Even after the formation of the United Nations in 1945 and the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 1995, the US could not be restrained.

Congress has, from time to time, issued a plethora of legislation with respect to sanctions and foreign policy that either authorises or mandates the US President, the US Department of the Treasury, or other federal departments to impose certain sanctions. The significant legislations are: Treasury's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), and the United Nations Participation Act (UNPA), Section 301 of the US Trade Act of 1974 -usually referred to as Super 301. Pursuant to IEEPA, the President can declare a national emergency and issue executive orders to address that national emergency by, among other things, freezing the assets of and prohibiting financial transactions with any country, entity or person determined to be a threat to the United States.

A threat to the international rule-based order

Repeated use of discriminatory policies, reciprocal tariffs, and unilateral sanctions used by the USA, that contravene WTO commitments, breaks the rule-based international order. Due to the prolonged non-cooperation of the USA, the Dispute Settlement Mechanism (DSM) of the WTO has become almost defunct.

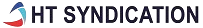

Economic sanctions have become central to US foreign policy. Over the past two decades, Washington has imposed more sanctions than the European Union, the United Nations, and Canada combined, with around seventy active sanctions programs targeting over 9,000 individuals, companies, and economic sectors worldwide. Early sanctions relied on broad trade embargoes and sectoral bans, but over time, policymakers shifted toward more nuanced financial measures designed to target specific firms, individuals, and sectors. A recent study (Dongan Tan, 2025) shows that sanctions-whether imposed unilaterally by the United States or multilaterally through international bodies-jumped sharply after 2010, with financial measures now outnumbering trade, arms, military, and travel restrictions. Data from the Global Sanctions Database (GSDB-R4), which tracks international sanction policies, identifies a total of 1,547 unique sanction cases involving the US between 1950 and 2023.

During the Cold War Era (1950-1990), Sanctions were used gradually and often took the form of comprehensive embargoes against nation-states, such as Cuba (1960) and North Korea (1950). But post-Cold War (1990s), there was a "major increase" in economic sanctions usage as they became a preferred tool for addressing human rights and arms proliferation. In the Modern Era (2000-19), the focus shifted to "smart" or targeted sanctions. The Obama administration added 655 designations for Iran alone, while the Trump administration saw US sanctions account for 40 per cent of all global sanctions by 2019.

A key distinction exists between multilateral and unilateral sanctions. The former, imposed primarily by the UN Security Council under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, are legally recognised enforcement mechanisms. By contrast, unilateral sanctions are widely considered unlawful. The US, which accounts for over 80 per cent of unilateral sanctions imposed globally, has increasingly relied on them as a foreign policy tool, with designations surging 933 per cent between 2001 and 2021. These sanctions now impact one-third of the global population across 30 countries, underscoring the weaponisation of dollar hegemony to advance US interests. Given the dominance of the US dollar in global trade, sanctioned nations face severe economic isolation and struggle to engage in commerce without access to the world's primary reserve currency, observes Jose Atiles (2025).

US unilateral sanctions are characterised by their extraterritorial application. That is, the US not only restricts its own companies and citizens from engaging with sanctioned states but also pressures third parties into compliance. The embargoes on Cuba (1962), Venezuela, Iran, and the Russian Federation are a few examples. Second, the US has often justified unilateral sanctions on the grounds of promoting democracy and human rights- examples, Iraq, Iran. Third, while US policymakers justify sanctions as targeted measures against authoritarian governments, their impact on civilian populations has been catastrophic. US sanctions on Venezuela have caused an estimated USD 22.5 billion in lost income since 2017. Studies indicate that US sanctions contributed to at least 40,000 excess deaths in a single year due to the collapse of public services and restricted access to medicine and food in Venezuela. Iran's gross domestic product (GDP) per capita fell from more than USD 8,000 in 2012 to about USD 6,000 by 2017, and to a little above USD 5,000 in 2024. The sharpest declines coincided with the tightening of US sanctions under Trump's campaign from 2018 onwards, which squeezed oil exports and access to global finance.

Trade analysts observe that the Trump Administration's embrace of power politics in the trade arena violates both the letter and spirit of the WTO's General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, undermining the integrity of the multilateral trading system. Though the US committed to respect thousands of binding tariffs, negotiated with the rest of the WTO membership as part of its acceptance of the WTO Agreement, it is disregarding these obligations by violating the core prohibition to unilaterally increase duties that have been capped. The bilateral deals also defy the quintessential purpose of the WTO - promoting multilateral negotiations - which can be carried out either on a product-by-product basis or on a more global scale. The US has also not paid its WTO membership fee for two years running (2023, 2024) and continues to cripple the dispute settlement system - the crown jewel of the agreement - by blocking the appointments of new Appellate Body judges, thereby undermining enforcement of the agreement. On April 26, 2024, the United States blocked a request from 130 members to fill the vacancies at the World Trade Organisation's Appellate Body (AB).

US sanctions on India

The US President, in an Executive Order 14329 of August 6, 2025, imposed an additional ad valorem rate of duty of 25 per cent on imports of articles of India, which, at that time, was directly or indirectly importing Russian Federation oil. Executive Order 14066 prohibited, among other things, the importation into the United States of certain products of Russian Federation origin, including crude oil, petroleum, and petroleum fuels, oils, and products of their distillation.

On February 6, the US President in an official communique mentioned that as 'India has committed to stop directly or indirectly importing Russian Federation oil, has represented that it will purchase United States energy products from the United States, and has recently committed to a framework with the United States to expand defence cooperation over the next 10 years', the US President modified the Executive Order 14329 eliminating the additional ad valorem rate of duty imposed on imports of articles of India.

The most obnoxious part of this declaration lies in section 4, titled: Monitoring and Recommendations, which states, "The Secretary of Commerce, in coordination with the Secretary of State, Secretary of the Treasury, and any other senior official the Secretary of Commerce deems appropriate, shall monitor whether India resumes directly or indirectly importing Russian Federation oil, as defined in section 7 of Executive Order 14329. If the Secretary of Commerce finds that India has resumed directly or indirectly importing Russian Federation oil, the Secretary of State shall recommend whether and to what extent I should take additional action as to India, including whether I should re-impose the additional ad valorem rate of duty of 25 per cent on imports of articles of India."

Reacting to US sanctions on India, the Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has accused the United States of attempting to prevent India and other countries from buying Russian oil, describing Washington's approach as coercive and aimed at achieving global economic domination.

Since the Iranian Revolution of 1979, the United States has used sanctions of various types as key tools of U.S. policy toward the government of Iran. U.S. sanctions on Iran block Iranian government assets in the United States, ban nearly all U.S. trade with Iran, and prohibit foreign assistance and arms sales. U.S. law authorises sanctions targeting Iran's energy sector, including foreign corporations that invest in it and entities that buy, sell, or transport Iranian oil; Iran's financial sector, including its Central Bank; and arms trade to or from Iran. On February 4, 2025, President Trump signed a National Security Presidential Memorandum directing the imposition of maximum pressure on Iran's government, including "a robust and continual sanctions enforcement campaign . that denies the regime and its terror proxies access to revenue. The 118th Congress enacted several Iran-related sanctions measures, mostly as part of the emergency national security supplemental passed in the wake of Iran's unprecedented direct attack against Israel in April 2024. Those measures included the SHIP Act, which directs the President to impose sanctions on port operators, refineries, and other entities linked to Iranian oil.

These US sanctions have severely impacted Indo-Iranian economic relations. India had to stop high-quality Iranian crude and almost abandoned the USD 500 million strategic Chabahar Port project, India's only reliable land bridge to Afghanistan and Central Asia, at a time when Pakistan blocks overland access, and China is rapidly expanding its footprint across West Asia. India's Adani Enterprises said (Tuesday, February 10) it was cooperating with a US probe into potential sanctions violations, after a media report alleged that the company had imported Iranian oil products through Mundra port and was looking into several tankers used to ship the fuel.

On February 6, the United States imposed new sanctions tied to a network moving Iranian oil. The move - which sanctions 15 entities, 14 vessels, and two individuals - targets Tehran's "shadow fleet," a covert shipping network that the Trump administration says helps Iran evade sanctions. Meanwhile, on February 5, the Indian Coast Guard intercepted 3 Sanctioned Oil Tankers Linked To Iran's 'Shadow Fleet' In Arabian Sea. The vessels, reportedly part of an Iran-linked "shadow fleet," were located about 100 nautical miles west of Mumbai while allegedly engaged in the illicit transfer of oil cargo within India's maritime jurisdiction. The seizure of three tankers carrying Iranian oil has raised diplomatic questions. Experts suggest the move may signal India's tacit alignment with US sanctions on Iran, despite them not being UN-mandated.

The recent sanctions on India for maintaining trade relations with the USA's enemy nations - the Russian Federation and Islamic Republic of Iran, the two most trusted friends of India for years, have put India on the mat. Incidentally, India, Russia, and Iran are members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) and the BRICS bloc, which are perceived as the major challengers to the US hegemony on the global economy and politics.

Apparently, US President Trump has been successful in luring India out of the China-led axis. Nonetheless, the stability of the Indo-US deal, negotiated under US threats, depends on how China and Russia react to these new US sanctions.

Published by HT Digital Content Services with permission from Millennium Post.